Egypt western desert fayoum whales valley

Egypt western desert fayoum whales valley The mammalian order Cetacea is divided into three suborders: (1) Oligocene to Recent Odontoceti or ‘toothed whales’— living today; (2) Oligocene to Recent Mysticeti or ‘baleen whales’— living today; and (3) older and more primitive Eocene Archaeoceti or ‘archaic whales’— which evolved from land mammals and gave rise to later odontocetes and mysticetes.

My research on the origin and early evolution of whales is focused on archaeocetes.

I have been fortunate to work with many colleagues on this in Egypt, Jordan, Pakistan, and India, (see co-authors in the publication list below).

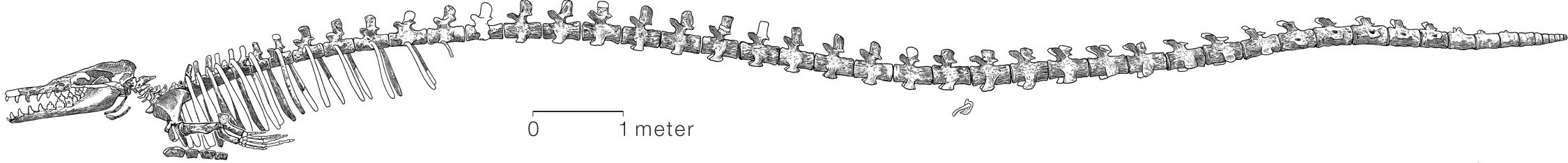

The stages of early whale evolution that we have documented are shown here in Figure 1.

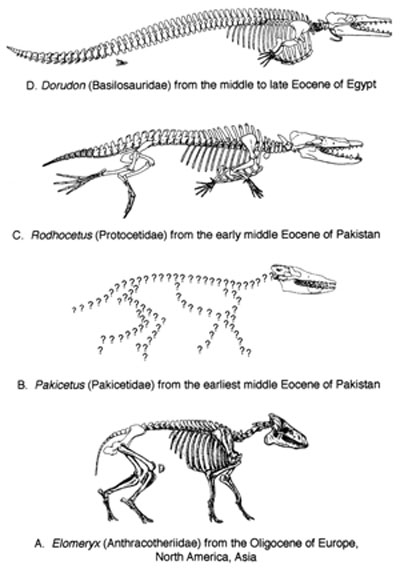

We have found and collected virtually complete skeletons of middle-to-late Eocene Basilosauridae (Dorudon and Basilosaurus), exceptionally complete skeletons of middle Eocene Protocetidae (especially Rodhocetus and Artiocetus), and a partial skull of earliest middle Eocene Pakicetidae (Pakicetus).

Recovery of diagnostic ankle bones in the skeletons of primitive protocetids during our field work in Pakistan in 2000 confirmed their derivation from Artiodactyla (the mammalian order including cows, deer, hippos, etc.), and showed convincingly that whales did not originate from mesonychid condylarths as Van Valen hypothesized (and we had expected).

{google_map}Egypt Fayoum wadi hitan{/google_map}

Egypt western desert fayoum whales valley Figure 1. Skeletons of the archaeocetes Dorudon atrox and Rodhocetus balochistanensis compared to that of Elomeryx armatus, which is here taken as a model for the extinct group of artiodactyls (Anthracotheriidae, s.l.) that we now think may have given rise to archaic whales.Pakicetus has a distinctive skull and lower jaw, but is not demonstrably different from early protocetids postcranially. Note changes in body proportions and elongation of feet for foot-powered swimming in Rodhocetus, then later reduction of the hind limbs and feet as the tail-powered swimming of modern cetaceans evolved in Dorudon.A. Elomeryx drawing from W. B. Scott, first published in 1894. B. Pakicetus skull from Gingerich et al. (1983). Terrestrial interpretation is pure speculation: what little is known of the skeleton resembles Rodhocetus. C. Rodhocetus skeletal reconstruction from Gingerich et al. (2001). D. Dorudon skeletal reconstruction from Gingerich and Uhen (1996). Figure may be reproduced for non-profit educational use. |

In the 1980s our field work on archaeocetes shifted to Egypt, to the classic but long-neglected site of Zeuglodon Valley or, today, Wadi Hitan.

Our camp in the desert in Wadi Hitan is shown in Figure 2, and investigation of a weathered Basilosaurus is shown in Figure 3.

Our most interesting discovery came in 1989, when we found that both Basilosaurus isis and Dorudon atrox retained feet and toes (see Figs. 4 and 5).

This discovery then led to renewed investigation of middle Eocene whale strata in Pakistan, starting in 1991, and focusing on on the Sulaiman Range where we had earlier joked about ‘walking whales’.

Egypt western desert fayoum whales valley

New whales named from Wadi Hitan and Fayum Province in Egypt include Ancalecetus simonsi (Gingerich and Uhen, 1996) and Saghacetus osiris (see Gingerich, 1992).

Figure 2. University of Michigan camp in Wadi Hitan, Egypt. This area, approximately 10 x 10 km, was studied in 1983, 1985, 1987, 1989, 1991, and 1993, during which time some 400 archaeocete and sirenian skeletons were found and mapped. These range in preservation from virtually complete specimens just being exposed by erosion to the last remnants of specimens destroyed by the wind. Photograph ©1991 Philip Gingerich. Figure may be reproduced for non-profit educational use. |

Figure 3. Dr. B. Holly Smith working at the base of the tail of a weathered Basilosaurus isis in Wadi Hitan, Egypt. We were particularly interested in this part of the skeleton because this is where the reduced hind limbs, feet, and toes were found (see Fig. 4). Photograph ©1991 Philip Gingerich. Figure may be reproduced for non-profit educational use. |

Figure 4. Ankle, foot, and toes of Basilosaurus isis excavated in Wadi Hitan, Egypt. This find was described in Gingerich et al. (1990). The foot as shown is approximately 12 cm long. Photograph ©1991 Philip Gingerich. Figure may be reproduced for non-profit educational use. |

Figure 5. Virtually complete skeleton of Dorudon atrox excavated in Wadi Hitan, Egypt. Note the retention of hind limbs, feet, and toes like those found in Basilosaurus. This find is described in Uhen (1996, 2004). The skeleton is approximately 5 m long. Photograph ©1998 Philip Gingerich. Figure may be reproduced for non-profit educational use. As outlined above, we worked at Wadi Hitan in Egypt from 1983 through 1993, and collected several unusually complete skeletons of 5-meter-long Dorudon atrox. We mapped many skeletons of the 18-meter-long serpentine Basilosaurus isis, but never had the resources to collect a skeleton. Attempts to interpret Basilosaurus have long been frustrated because no one ever collected a complete skeleton anywhere. The classic Basilosaurus cetoides from Alabama restored by Gidley, 1913, and Kellogg, 1936— on exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.— is a composite of two partial skeletons with important parts missing or borrowed from other marine mammals.

Study of Basilosaurus took a major step forward in 2005 when an important skeleton of B. isis was collected in Wadi Hitan. Later the same year, Wadi Hitan was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its natural beauty and importance for understanding whale evolution. By prearranged agreement, the new Basilosaurus skeleton is to be prepared, studied, and then returned to Egypt for exhibition. The skeleton is expected to play an integral role in the educational development of Wadi Hitan.

Egypt western desert fayoum whales valley

Egypt western desert fayoum whales valley

|